Carlisle cathedral

Contents |

[edit] Introduction

Carlisle's cathedral, small in scale but significant in many ways, played an important role in the region's long - and sometimes turbulent - history.

[edit] History

Carlisle cathedral was initially a modest Norman priory church built in 1122 over the ruins of an existing structure. Some portions of this Norman church remain in the south transept and two bays of the nave, although much of it has been destroyed or removed over the centuries.

Constructed from local red sandstone (which would prove to be an ongoing issue due to its tendency to become misshapen and discoloured over time), the church has gone through a series of changes. From the time it was constructed, the building’s piers slowly started to to lean as a result of subsidence, and its structural supports started to sink into the marshy land.

The first renovation began in the 13th century during the reign of Edward I who held his parliament in Carlisle and worshipped at the cathedral. These modifications in the Gothic style expanded the cathedral and changed its orientation. However, this work was severely damaged shortly after its completion in 1292, when a fire was intentionally set in the city by a man upset about a legal matter that was not decided in his favour. The fire spread to the cathedral and caused significant damage that took several decades to repair. However, the Norman tower subsequently collapsed onto the north transept.

[edit] The east window

By about 1350, one of the most important features of Carlisle cathedral was complete. The east window, with its elaborate tracery and glass, is still thought to be the largest in the Flowing Decorated Gothic style in England.

|

| The stained glass and tracery of the east window of Carlisle cathedral. |

The east window is thought to be the work of Ivo de Raughton, considered one of the most accomplished architects of decorative tracery in Northern England at the time.

While the upper portion of the window is original, the lower nine sections were created by John Hardman and date from 1861. They were installed as replacements for medieval windows removed at the time of the Civil War.

[edit] The curse of Carlisle

Renewal of the monastic buildings continued in the 15th and early 16th centuries, but in 1525, there were new troubles in Carlisle. The city’s association with the Border reivers (a group of thieves and raiders who caused chaos along the border between England and Scotland), resulted in the Archbishop of Glasgow issuing a 1,000+ word curse on the city.

|

| The cursing stone is carved with the words of the Archibishop of Glasgow. It is on display at Tullie House, Carlisle. |

This legendary pronouncement became linked to misfortunes that occurred in Carlisle (including floods, diseases, business failures and even misfortunes associated with the Cathedral).

Like many churches, Carlisle cathedral was damaged during the English Civil War. The Scottish Presbyterian Army took the opportunity to destroy part of the nave and used the stones to fortify Carlisle Castle. They also demolished the cloister and chapter house during and removed a modest spire.

During the Jacobite rebellion, the remaining portion of the nave was briefly used as a prison, but no further damage was inflicted on the building.

[edit] Restoration by Ewan Christian

Following several clumsy renovations during its nine century history, Carlisle cathedral was finally given an extensive restoration between 1853 and 1870. Undertaken by Ewan Christian (the British architect and one time president of the RIBA best known for his design of the National Portrait Gallery), this lengthy project preserved some of the original noteworthy characteristics of the building and added some new ones.

|

| The Carlisle cathedral ceiling by Owen Jones (1856). |

It was during this period that Owen Jones updated the ceiling based on the original medieval style. Considered one of the finest decorative artists of the period, Jones came up with a detailed motif that featured angels and stars.

The ceiling was most recently refurbished in 1970, and the east window was restored in 1982.

[edit] Related articles on Designing Buildings

IHBC NewsBlog

Latest IHBC Issue of Context features Roofing

Articles range from slate to pitched roofs, and carbon impact to solar generation to roofscapes.

Three reasons not to demolish Edinburgh’s Argyle House

Should 'Edinburgh's ugliest building' be saved?

IHBC’s 2025 Parliamentary Briefing...from Crafts in Crisis to Rubbish Retrofit

IHBC launches research-led ‘5 Commitments to Help Heritage Skills in Conservation’

How RDSAP 10.2 impacts EPC assessments in traditional buildings

Energy performance certificates (EPCs) tell us how energy efficient our buildings are, but the way these certificates are generated has changed.

700-year-old church tower suspended 45ft

The London church is part of a 'never seen before feat of engineering'.

The historic Old War Office (OWO) has undergone a remarkable transformation

The Grade II* listed neo-Baroque landmark in central London is an example of adaptive reuse in architecture, where heritage meets modern sophistication.

West Midlands Heritage Careers Fair 2025

Join the West Midlands Historic Buildings Trust on 13 October 2025, from 10.00am.

Former carpark and shopping centre to be transformed into new homes

Transformation to be a UK first.

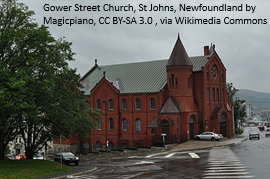

Canada is losing its churches…

Can communities afford to let that happen?

131 derelict buildings recorded in Dublin city

It has increased 80% in the past four years.